|

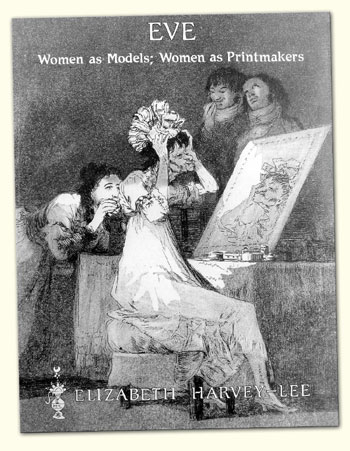

EVE

Women

as Models; Women as Printmakers Women

as Models; Women as Printmakers

While

women printmakers are scarcely recorded till the 17th

century, images of women date from the very earliest

days of printmaking. From c1390 they are portrayed

in incidents from the life of the Virgin and as images

of holy saints, produced as woodcuts for convents and

centres of pilgrimage. In secular imagery they appear

on playing cards and tarot cards. In intaglio prints

they appear in similar contexts from c1440.

Already

from the later 15th century occasional examples are

found of genre scenes with knights attending ladies,

rustic courting and merriment in taverns, and even

studies of women’s heads, though not defined

portraits. Many of the genre scenes were intended to

be symbolic of the transience of life.

By

the 16th century women were being portrayed in many

roles. The development of book illustration extended

the diversity of range. Though the majority of prints

still represented biblical passages from the old and

new testaments, the Renaissance introduced new or parallel

themes from the classical mythology of ancient Greece

or Rome; or from contemporary authors such as Dante

or Boccaccio; or drawn from the more homely advice

proffered in emblem books. In this way, particularly

in northern Europe, where artists tended to transpose

biblical scenes to a contemporary setting, every aspect

of life and relationships between the sexes came to

be interpreted in print. The Renaissance awareness of

the temporal, the individual and history led to the

development of the portrait, both male and female.

Renaissance,

Mannerist and Baroque prints of women can thus be enjoyed

on several levels. Iconography offers an enormous scope

of intellectual concepts, which yet can be couched

in the manners, dress and customs of everyday life.

Accepted timeless truths are presented in the reality

of the artist’s own time. The artist’s

family is a mirror of the Holy Family. Examples such

as 'Samson & Delilah' and 'Judith & Holofernes',

demonstrate the power women can gain over men. Certain

aspects of moral worth and religion, abstract ideas

of truth, justice and beauty, counterbalanced by evil,

deceit and envy, are demonstrated through the female

form. Giving gender to inanimate objects and persona

to abstract concepts, according to characteristics

recognised by mankind as essentially male or female

is inherent in human thought. Most Latin and Germanic

languages still designate nouns as masculine or feminine.

However had society been dominated by women in classical

times would Beauty be personified as a man rather than

a woman?

By

the close of the 18th century artists were beginning

to approach the imaging of women differently, demonstrated

in the work of Goya, last of the Old Masters and first

of the Moderns. Goya anticipated the satire of Daumier

and the impressionism of Manet.

In

the modern period artists have tended to delight in

the individual model herself and the technical and

stylistic means of achieving their desired expression.

No longer an ostensibly elevated intention of purpose

was felt necessary for the excuse of depicting the

female form; Venus abdicated while Leda vanished. Eve

was no longer reprehensible for the fall of man. The

Impressionists were artist-reporters, their eyes objective

even when affectionate. Paris was the centre of the

art world and the Parisienne, whether gamin,

trottin, grande dame or simply

femme, whether

wife, mother, companion, sister, mistress or other

role, epitomised the art of the period, to such an

extent that in her honour the end of the 19th century

is called La Belle Epoque.

However

the modern period has its dichotomies. The dialogue

between the naturalistic 'real' and the 'ideal' had

followers on both sides. The pre-Raphaelites and their

followers in England and later the Symbolists in France

and Germany demanded more of the medium than art for

art’s

sake or a small piece of reality encapsulated. They

sought a distillation of eternal truth, which was also

most frequently expressed through an image of womankind.

In

Modern British printmaking of the early decades of

the 20th century some artists specialised in images

of women, most specifically Brockhurst and Russell

Flint; for others the subject was incidental though

responsible for the occasional memorable female image. In

Modern British printmaking of the early decades of

the 20th century some artists specialised in images

of women, most specifically Brockhurst and Russell

Flint; for others the subject was incidental though

responsible for the occasional memorable female image.

Until

the most recent times, it has long been acknowledged

that women excel at the literary and musical arts

but do not in general attain the same achievement in

the plastic arts. Did these require a single-mindedness

to which most women in the past have been unable to

commit themselves and instead the relationships and

demands of family life have taken priority? Käthe

Kollwitz recognized in herself a bi-sexuality and put

her artistic self down entirely to the masculine in

her make-up. It is noticeable that it is only in the

20th century, when women are socially and economically

free as never before to lead independent lives, that

women artists have proliferated.

Though

nuns may have contributed to the incunabula of printmaking,

historically women do not get recognized as printmakers

until the 17th century, and then names are still very

few. The likes of Geertruyd Roghman, Magdalena van

de Passe and Claudine Stella all tended to be from

families of engravers and pupils of their fathers,

uncles or brothers. Their work however holds it own.

Most were from Holland or France, though Elisabetta

Sirani was an Italian exception. Occasionally widows,

though not practising printmakers, took over their

husband’s print publishing activities. In the

18th century one is aware only of Angelica Kauffman,

working in England; but the century as a whole was

dominated by reproductive engraving rather than original

printmaking by either sex.

Women

play an increasingly larger role as printmakers from

the later decades of the 19th century onwards, when

independent art education became available to them.

Women such as Berthe Morisot, Mary Cassatt, Käthe

Kollwitz, Paula Modersohn-Becker, Sonia Delaunay, Marie

Larencin and Laura Knight have international reputations

as artists, in the unisex context of art history.

It

is interesting to note that in modern British wood

engraving women made a significant contribution. Gwen

Raverat, Clare Leighton, Agnes Miller Parker and Gertrude

Hermes were among the leading exponents in the medium.

Ultimately

the sex of an artist, like his or her race, religion

or individual lifestyle, is irrelevant. It is the work

that is of importance; the recognition of the initial

concept, its successful achievement as a print, the

combination of imagination and technique to create

a memorable, significant and meaningful image.

This said, the ‘sex’ of an unfamiliar print,

signed only with an initial rather then the give-away

first name of the artist, can frequently be ‘guessed’ correctly,

for a certain indefinable ‘feminine’ sensibility

does often inform images made by women.

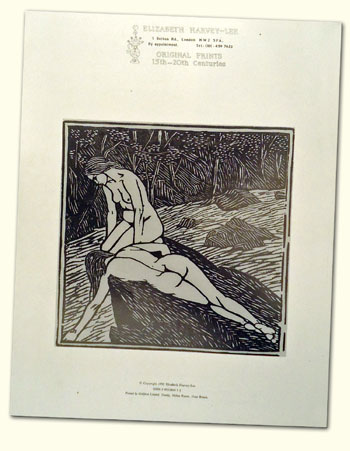

Published

1992.

52 pages, 138 items described and illustrated.

(Out

of print)

|

|

Artists

included in the catalogue:

Women artists

are in bold

- Altdorfer

A.

- Auerbach

A.

- Austin

F.

- Austin

R.S.

- Bacon

M.M.

- Belleroche

A.

- Bertram

M.

- Besnard

A.

- Binyon

H.

- Blakely

Z.

- Bonasone

G.

- Bonfils

R.

- Bosse

A.

- Boutet

H.

- Brockhurst

G.L.

- Brouet

A.

- Brown

D.

- Brusenbauch

A.

- Buckton

E.

- Buckland-Wright

J.

- Cameron

K.

- Chahine

E.

- Clanence

J.

- Claus

E.

- Clegg

C.

- Collaert

H. (J.B.)

- Copely

J.

- Corinth

L.

- Cottet

C.

- Cursiter

S.

- Dalrymple

A.

- Daumier

H.

- Drury

P.

- Dusart

C.

- Dyck

A. van

- Einschlag

E.

- Farleigh

J.

- Farmer

M.M.

- Flint

W.R.

- Freeth

H.A.

- Frood

H.

- Gabain

E.

- Gavarni

P.

- Gheyn

J. de

- Gill

E.

- Goeneutte

N.

- Goldthwaite

A.

- Goltzius

H.

- Gosse

S.

- Goya

F.

- Grammaté W.

- Grant

J.

- Guignuet

F.J.

- Hislop

A.H.

- Hofmann

L. von

- Holmes

K.

- Hunt

W.H.

- Huys

F.

- Israels

J.

- Jacque

C.E

- Jacquemart

J.

- Jeanniot

P.G.

- Jode

P. de

- Kirchner

E.

- Knopff

F.

- Kolb

A.

- Kollwitz

K.

- Laurent

E.

- Lee-Hankey

W.

- Legrand

L.

- Legros

A.

- Leighton

C.

- Lunois

A.

- Maillol

A.

- Meid

H.

- Millais

J.E.

- Molitor

M.

- Moran

M.N.

- Morisot

B.

- Nash

J.

- Neumont

M.

- Orovida

- Passe

M. van de

- Paterson

V.

- Picasso

P.

- Pissarro

L.

- Pissarro

O.

- Pryse

G.S.

- Ranft

R.

- Raverat

G.

- Robinson

M.C.

- Roghman

G.

- Rops

F.

- Roussel

T.

- Rousselet

G.

- Runciman

A.

- Sadeler

G.

- Sadeler

R.

- Saenredam

J.

- Schmutzer

F.

- Sherlock

M.

- Sparks

N.

- Staeger

F.

- Steinlen

T.A.

- Stella

C.

- Valadon

S.

- Vertès

M.

- Vigano

V.

- Vincent

B.

- Vuillard

E.

- Waterhouse

J.W.

- Wolff

H.

- Zorn

A.

Return to the top |